The Soul of the Shanghai World’s Fair aptured

Since 1970, Dr. T. F. Chen has held more than 200 one-man shows in Asia, Europe, and the Americas. Dr. Chen’s recent and current exhibitions include:

2015 年 9 月 29 日T.F. CHEN“Post Van Gogh Series”

2015 年 10 月 14 日The Soul of the Shanghai World’s Fair aptured

Lawrence Jeppson (an art consultant, historian, curator, writer, editor, publisher, lecturer, and appraiser.)

As we go deeper into the 21st century, Dr. Tsing-fang Chen stands alone as the most important artist working the world stage today. By comparison, any other living artist you encounter--in exhibitions or examined in the media--is parochial, working within a narrow esthetic and cultural range.

As a world-class artist Chen is Number One. Atop that pinnacle, he is alone.

There is no doubt in my mind that in time Chen’s paintings are destined to be found in every significant public, corporate, or private collection in the world. Every great museum that recognizes 20th and 21st century art will scramble to add his work to their collections.

Using his brilliant gifts of color, composition, and philosophical genius, Chen continues to create an astounding universe which examines anything and everything going on in the world. He cunningly unites past, present, and future. He makes use of every available visual icon to create Chen’s World of juxtaposed, colorful, vibrant, and exciting visions. Chen is a recorder, interpreter, and fore-teller of what is going on in the world–and in human hearts and brains.

Chen’s brilliant torrent of great paintings has brought him high recognition as “Cultural Ambassador for Tolerance and Peace Through the Arts” from the United Nations.

His suite of paintings Towards the 21st Century, Symphony of World Culture, a towering group of end-to-end canvases measuring 110" high by 560" in total length, is the most prodigious work of contemporary painting that I know of. (Its closest counterparts in art would be in modern French tapestries, Jean Lurçat’s monumental group La Chant du Monde and Mathieu Mategot’s only partially realized series Visions of Space. Both artists are deceased.)

The Chen creations are possible because they cascade from a man whose formation is deeply rooted in the East and expanded in the West. He is not a bridge between East and West but a shrewd, perceptive amalgamater of both. He is not only on the world stage; he is the world stage.

Chen accomplishes this by taking images from every source–any art, old or new, any period, history, archaeology, geography, news events, philosophy, imagination. Any thing the eye can see has the potential to become one of his building blocks. He blends these blocks into new visions that the eye has never seen before.

Every Chen painting exists on several levels. The first is a kind of visual pleasure or disruption. Usually the former. It is made up of composition and color. Sometimes these paintings seem simple enough. Sometimes composition and color are extremely complex. But lurking below the surface of immediate esthetic pleasure or displeasure are myriads of meanings. Why is Chen saying this? What does this mean? The viewer is enticed to think and respond. These responses may change every time the viewer looks at the painting. There are always new things to perceive, new ways to understand. And that is the essence of great art–repeated esthetic discovery and emotional/intellectual stimulation.

Chen’s art life began as a conflict between his Chinese heritage bred in his native Taiwan and his encounter with Western art and thought, especially during a dozen years in Paris. Was he an Oriental or an Occidental? He began trying to blend the two, a blending which achieved its public focus at his first museum exhibition in America, at the Philadelphia Art Alliance in 1978, and the coinage of the word Neo-Iconography to describe his art. The show and the label helped the world to crystallize its understanding of what Chen was doing, and perhaps it helped the artist to understand as well.

An interesting side-bar about Chen is that although his Neo-Iconography makes him the great world painter, he is also brilliant when he paints landscapes, Formosan folklore, city streets and buildings, and interpretive portraits.

A few years after Philadelphia, Chen became caught up in the coming centennial of the Statue of Liberty, 1888-1988. He had seen Liberty on his fist visits to the United States from France and when he came as a new emigrant, which would lead to his American citizenship. If the Statue of Liberty was going to be 100 years old, he would create 100 paintings as an appropriate commemoration. Every painting would be a different interpretation, and these paintings would employ a slew of icons. I had the honor of writing the lead article to the colorful exhibition catalog. It is appropriate here to quote two paragraphs from that introduction:

The eye-popping cargo of Liberty litanies is also a hosanna to the flowering of Neo-Iconography, which is a limitless way of uniting time and space and esthetic diversity into fresh artistic expressions and insights. Neo-Iconography can make us think, feel, and even laugh.

As the Prophet, Seer, and Revelator for Neo-Iconography, Chen appropriates visual images from man’s treasury of art and experiences and imaginatively molds them into beautiful and powerful new paintings. These paintings reward us with fresh thrills and insights without cutting us off from our visual heritage. . .he has bound together, in a saturated vision, the cultures of Asia, Europe, and America to create this astonishing tribute to the Statue of Liberty.

The number of different icons utilized in the Liberty series is in the hundreds.

Other centennials were coming.

The Eiffel Tower in Paris was only a year younger than the Statue of Liberty. It was erected for the World’s Fair of 1889. Chen had studied and painted in Paris for a dozen years. He knew and loved Gustave Eiffel’s iconic metal machination. This required another 100 paintings. With so little time between the Liberty and Eiffel centennials, Chen had to paint night and day. It was helpful that his wife Lucia was a genius of another kind, a collaborator who understood the importance of her husband’s work and could manage the family and commerce in such a way as to allow him full attention to his painting.

Hard on the heels of the Liberty and Eiffel centennials came the 100th anniversary of Vincent Van Gogh’s death, 1990. Another 100 paintings were needed. This towering Dutch/French Post-impressionist is one of Chen’s favorite artists, and a myriad of Van Gogh shards find homes in Chen’s paintings. So Chen went to his easels and in white-hot frenzy painted the 100 paintings commemorating the artist’s passing from the scene. Like the Liberty 100 and the Eiffel 100, the Van Gogh 100 sizzled and snapped. They achieved the homage Chen sought. The paintings were exhibited and widely acclaimed in the Netherlands. And other places.

Chen set out to do 100 paintings about Las Vegas, Nevada, sometimes referred to as “Sin City” because of its gambling, divorce access, and flamboyant visual shatterings. Chen was not doing this as a homage, as he had done in the three previous 100-painting floods, but as an exploration of the Vegas visual cacophony and all its comic and social ramifications. I believe Chen abandoned this pursuit before it reached 100, as he found worthier subjects.

A worthier subject was the 2008 Olympic Games held in Beijing. Again, 100 paintings, maybe more. The best athletes came from all over the world, and China put on a fabulous show. Here again, as in the United Nations work, Chen proved himself a world-class artist. There were tensions, successes, failures in the diverse events. In the totality there was great excitement and great success. Hundreds of photographers shot every event and painters put some of the individual achievements on canvas or computer-generated images, but only Chen succeeded in doing the whole Olympics, capturing and lifting their spirit in visual extravaganza.

Not everyone could be at the Games, but Chen’s work is forever memorialized in the very big book Dr. T. F. Chen’s Art & the Olympics: an Art for Humanity, published in Chinese and English.

Hard on the heals of the Olympics, the excitement in China moved south, to the 2010 Shanghai Worlds’ Fair.

In a lifetime of more than eight decades I have been privileged to view art at International Expositions (World’s Fairs) in San Francisco, Bruxelles, Seattle, Montreal, and New York; at big-time international art fairs in New York, Washington, Paris, Basle, Venice, and Madrid; at hundreds of museums and galleries in the United States, Canada, Europe, and Asia. These have given me a wide, profound, and varied experience, visiting and thinking about man’s artistic means and manipulations over several millennia.

As I think back over these many manifestations, I see that most of them were narrow in scope. ARCO in Madrid, the Basle Art Fair, the Biennale in Venice are all composed of individual pavilions or booths which, usually, fixate on a single painter or a small national group.

Many of the most impressive museum shows to penetrate my lasting consciousness have been one-man retrospectives: Jan Vermeer at the National Gallery, Washington, Emile Nolde in a museum in Tokyo, James Rosenquist at the Houston Museum, and Jasper Johns at the Reina Sophia in Madrid.

Naturally, most of the art pavilions at the world’s fairs tend to be nationalistic, and the most prominent artistic manifestations tend to be architectural: the Atomium in Bruxelles, the Space Needle in Seattle, the Buckminister Fuller Geodesic Dome in New York.

Then came the World’s Fair to trump all World’s Fairs: the massive, encompassing, and pulsating Shanghai World’s Fair of 2010. And unlike all these other manifestations I have alluded to, there was a single artist with the skill, intelligence, and stamina to make a binding interpretation of the entire fair. No souvenir book of photographs (or scholarly examination for that matter) will ever approach the vivacity, beauty, understanding, drama, and intellectual and emotional penetration as the 100 paintings of the Fair done by Dr. Tsing-fang Chen, a Taiwanese American.

Chen is without peer. He is the most intellectually and internationally challenging artist at work anywhere in the world today. Although organized to show the world, including itself, China’s place in the world, the six-month Fair, more than any other ever organized, showed off the global world and its myriad cultures, that whole world of which China is a part. Chen set about to capture the entire spirit of the Fair and its many breath-taking components. So far as I am aware, no one has ever done this for any previous World’s Fair, Art Fair, or museum/gallery manifestation.

Chen accomplished this by studying each pavilion, its outward symbols, its inner meaning, its people, its places, its reality, and its aspirations. Then, using his brilliant mind and his highly developed genius for finding and combining a plethora of icons, he painted a philosophical and esthetic portrait of each of the pavilions, one by one.

When taken as a body, this collection of paintings captures, more than any photographic reportage can ever do, the soul of the Fair.

An icon can be any visual entity. Chen’s genius does not rest just on his ability to choose icons. The genius also demands visual success in depicting and arranging these icons and in the artist’s extraordinary command of compositional color. Chen’s bright and juxtaposed colors jab right into the heart of emotional responses. Few painters have that gift.

Because of the paintings’ complexities, viewers many not immediately recognize everything they are seeing. That is one of the marvels of great paintings: a viewer can always find something new not seen before. But to help viewers see new things and better understand what they are beholding, Julie Chen, daughter of Tsing-fang and Lucia, has developed an acute and concise way of unlocking keys to many of her father’s paintings. Father and daughter both have gifts for the world, as does the Chen’s son, Ted and his term produce giclée limited edition of Chen’s work.

Chen’s interpretations of the World’s Fair pavilions give us a suite of exciting paintings that have captured the world, one oil at a time. For many viewers, paintings they like most will be the ones that come closest to their own culture. The ones they should study hardest are ones that bring them new understanding. Because of space limitations, from this flow of extraordinary art I can mention only a few for my special comments.

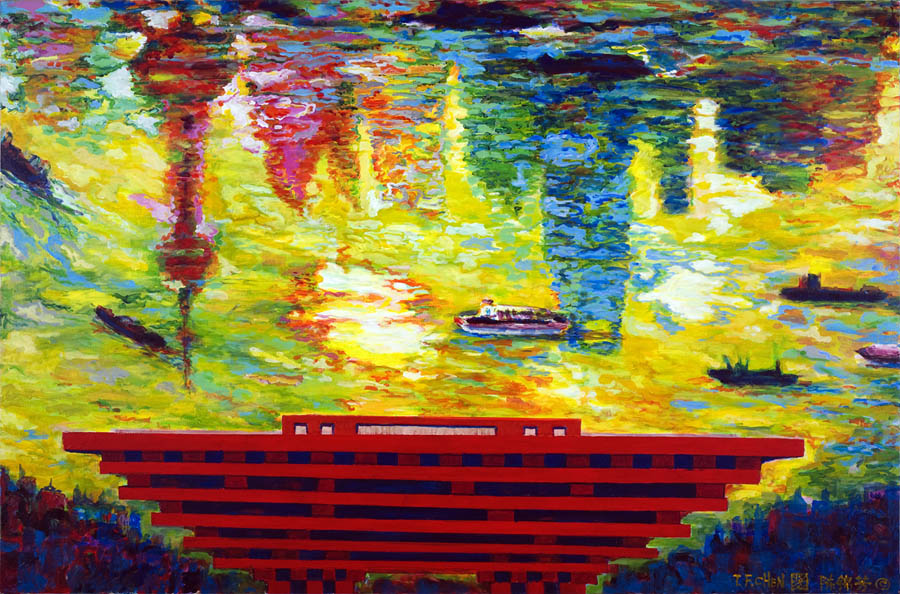

As one would expect, one of the most arresting paintings of these 100 is the depiction of the host city, Shanghai.

Shanghai. Shanghai is composed of four, maybe five, irregularly shaped horizontal bands of images. The top band shows a sky full of fireworks, clear across the width of the painting. Its architectural images begin, on the left, with yellow steps leading up to a red box and then the reversed terrace of an immense overhanging roof of the xxxxxxxxxxxxx. In the center of the widening first band is the Oriental Pearl TV Tower, with its three metallic spheres–a dance hall, a rotating restaurant, and an observation deck-- reassembling jewels. Chen has interpreted this structure in bright yellow and red, and it could just as easily be imagined as a rocket ready for liftoff, either way being a symbol of high technological achievement. To the right, in bright colors is a grouping of skyscrapers, which bring to mind the 88-story Jinmao Tower, the 110-story Shanghai World Financial Center, and the 120-floor Shanghai Tower, among many skyscrapers that show just how far the world’s most populous city has come from a sleepy fishing village in just over a century.

This top band ends on the right in a large oval, like a picture frame, across the middle of which is an icon of the new Lupu Bridge, the world’s longest arch bridge. To the left, and closer to the eye, a large river crane, animated and ready to work any of the freighter craft that ply the waterway. The river is painted bright red, color of good luck, and the sky above the bridge is bright sun-light yellow.

The next band down is a closer paean to Shanghai’s passion for skyscrapers, among them the historic Clock Tower Building, which houses Shanghai’s Museum of Art. This band of buildings is depicted in bright, bright colors against dark, dark blue sky. The brightly lit buildings are built shoulder to shoulder and could be imagined as a band of blinding battlements.

The third band changes scale. It is personalized, humanized. It begins with a pretty girl in party dress, then dancing couples enjoying a dance band, and next another pretty girl in red dress playing a stringed instrument.

The fourth and fifth bans are narrow and seem to merge. On the left, in the largest area of green in the painting, is an icon which may suggest a farm, and next to it several old-time, blue-roofed, white buildings along a river. The merged bands end in a large, traditional gate and a summoning of the Yu Yuan Garden, started in 1559 during the Ming dynasty.

France. The painting inspired by the French pavilion is the least complicated of Chen’s Fair outpourings. Its arresting elements are interpretations of two of the most famous sculptures by the most-highly esteemed sculptor of the modern age: August Rodin’s The Thinker, painted in bronze, and The Kiss, painted in gold. The Kiss, the passionate depiction of a couple in love was originally intended as an element of Rodin’s complex Gates of Hell, but the sculptor gave it an independent existence. The Thinker reveals a man in sober meditation battling powerful inner turmoil. The two sculptures and Chen’s selection of them for this painting dramatize a human confict between two necessary forces, passion and thought. By putting the images on the top of a roof, Chen emphasizes their overpowering importance.

Taiwan. This painting is a glorious amalgam of icons, but it is so excitedly pleasing that it is completely unnecessary to recognize any of those icons to appreciate its wonder. In the lower corners are three costumed figures, which many viewers will recognize, and between and above them cartouches jammed with abbreviated images. The top half of the canvas is a deluge of lighted lanterns, each with its own succinct calligraphy, which will give a dimension to the painting for Chinese viewers that the rest of us will not grasp. That will not lessen our appreciation for the wonders of the painting. Even Chen’s signature centered on the base of the painting becomes an integral icon of the composition.

Coca-Cola. Not all of the pavilions were national. Among the many commercial pavilions, Chen has selected Coca-Cola. Coke had modest beginnings. In 1886, John Pemberton, proprietor of Eagle Drug and Chemical, a drugstore in Columbus, Georgia concocted a non-alcoholic beverage after the county passed a law banning alcohol. From that start, Coke bottling plants have sprung up all over the world. Today Coke is sold in 200 countries, making it the most ubiquitous product on the planet. In the process Coca-Cola swallowed up dozens of other beverage makers including Minute-Maid and Fanta and hundreds of products. A visitor to the World of Coca-Cola museum in Atlanta, Georgia can sample 60 of the company’s products, many of which are concocted to accommodate local taste. In this painting Chen has made 54 interpretations of the Coca-Cola bottle from around the world. On the surface, this painting might call to mind American Pop Art, but where artists like Andy Warhol made slavish, repetitive replications of common products, every Chen bottle is vibrantly alive and different. Some are a mixture of icons. This painting is a lot of fun!

Australia–like a large island surrounded by the blue of oceans and wild birds, which suggest freedom. The island itself is more in the shape of Ayer’s Rock than the actual continent. The rock itself is alive with an amalgam of icons which suggest Australia’s varied geography, history, and cultures.

Shanxi summons up history that archaeologically goes back 180 million years up to the current day. Its colors are alive in contrasts and eyeful juxtapositions.

Macau’s colors and composition brim with the excitement of the place, and the Gansu depiction merges the cultural importance of place, dramatized by the dancers, with a sweeping encapsulated view of a modern city, while the Nepal canvas by contrast is one of Buddhist serenity and enlightenment.

One of my favorites, because of its compositional color, is the Shanghai Corporate Joint Pavilion interpretation, even though its icons are fewer and muted. In contrast the dramatic Republic of Korea is so chock-full of icons that there are almost too many to count, making it a painting which will be looked at and marveled over many times.

Lawrence Jeppson has been a renowned international art and art investment consultant, historian, curator, writer, editor, publisher, lecturer, and appraiser for nearly half a century.. Through the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service, the American Federation of Arts, NY’s Museum of Modern Art, and his own Art Circuit Services; Jeppson has been a contributor to more than 200 art exhibitions around the world.

The Soul of the Shanghai World’s Fair Captured

Lawrence Jeppson (an art consultant, historian, curator, writer, editor, publisher, lecturer, and appraiser.)

As we go deeper into the 21st century, Dr. Tsing-fang Chen stands alone as the most important artist working the world stage today. By comparison, any other living artist you encounter–in exhibitions or examined in the media–is parochial, working within a narrow esthetic and cultural range.

As a world-class artist Chen is Number One. Atop that pinnacle, he is alone.

There is no doubt in my mind that in time Chen’s paintings are destined to be found in every significant public, corporate, or private collection in the world. Every great museum that recognizes 20th and 21st century art will scramble to add his work to their collections.

Using his brilliant gifts of color, composition, and philosophical genius, Chen continues to create an astounding universe which examines anything and everything going on in the world. He cunningly unites past, present, and future. He makes use of every available visual icon to create Chen’s World of juxtaposed, colorful, vibrant, and exciting visions. Chen is a recorder, interpreter, and fore-teller of what is going on in the world–and in human hearts and brains.

Chen’s brilliant torrent of great paintings has brought him high recognition as “Cultural Ambassador for Tolerance and Peace Through the Arts” from the United Nations.

|

|

His suite of paintings Towards the 21st Century, Symphony of World Culture, a towering group of end-to-end canvases measuring 110″ high by 560″ in total length, is the most prodigious work of contemporary painting that I know of. (Its closest counterparts in art would be in modern French tapestries, Jean Lurçat’s monumental group La Chant du Monde and Mathieu Mategot’s only partially realized series Visions of Space. Both artists are deceased.)

The Chen creations are possible because they cascade from a man whose formation is deeply rooted in the East and expanded in the West. He is not a bridge between East and West but a shrewd, perceptive amalgamater of both. He is not only on the world stage; he is the world stage.

Chen accomplishes this by taking images from every source–any art, old or new, any period, history, archaeology, geography, news events, philosophy, imagination. Any thing the eye can see has the potential to become one of his building blocks. He blends these blocks into new visions that the eye has never seen before.

Every Chen painting exists on several levels. The first is a kind of visual pleasure or disruption. Usually the former. It is made up of composition and color. Sometimes these paintings seem simple enough. Sometimes composition and color are extremely complex. But lurking below the surface of immediate esthetic pleasure or displeasure are myriads of meanings. Why is Chen saying this? What does this mean? The viewer is enticed to think and respond. These responses may change every time the viewer looks at the painting. There are always new things to perceive, new ways to understand. And that is the essence of great art–repeated esthetic discovery and emotional/intellectual stimulation.

|

|

Chen’s art life began as a conflict between his Chinese heritage bred in his native Taiwan and his encounter with Western art and thought, especially during a dozen years in Paris. Was he an Oriental or an Occidental? He began trying to blend the two, a blending which achieved its public focus at his first museum exhibition in America, at the Philadelphia Art Alliance in 1978, and the coinage of the word Neo-Iconography to describe his art. The show and the label helped the world to crystallize its understanding of what Chen was doing, and perhaps it helped the artist to understand as well.

An interesting side-bar about Chen is that although his Neo-Iconography makes him the great world painter, he is also brilliant when he paints landscapes, Formosan folklore, city streets and buildings, and interpretive portraits.

A few years after Philadelphia, Chen became caught up in the coming centennial of the Statue of Liberty, 1888-1988. He had seen Liberty on his fist visits to the United States from France and when he came as a new emigrant, which would lead to his American citizenship. If the Statue of Liberty was going to be 100 years old, he would create 100 paintings as an appropriate commemoration. Every painting would be a different interpretation, and these paintings would employ a slew of icons. I had the honor of writing the lead article to the colorful exhibition catalog. It is appropriate here to quote two paragraphs from that introduction:

The eye-popping cargo of Liberty litanies is also a hosanna to the flowering of Neo-Iconography, which is a limitless way of uniting time and space and esthetic diversity into fresh artistic expressions and insights. Neo-Iconography can make us think, feel, and even laugh.

As the Prophet, Seer, and Revelator for Neo-Iconography, Chen appropriates visual images from man’s treasury of art and experiences and imaginatively molds them into beautiful and powerful new paintings. These paintings reward us with fresh thrills and insights without cutting us off from our visual heritage. . .he has bound together, in a saturated vision, the cultures of Asia, Europe, and America to create this astonishing tribute to the Statue of Liberty.

The number of different icons utilized in the Liberty series is in the hundreds.

Other centennials were coming.

The Eiffel Tower in Paris was only a year younger than the Statue of Liberty. It was erected for the World’s Fair of 1889. Chen had studied and painted in Paris for a dozen years. He knew and loved Gustave Eiffel’s iconic metal machination. This required another 100 paintings. With so little time between the Liberty and Eiffel centennials, Chen had to paint night and day. It was helpful that his wife Lucia was a genius of another kind, a collaborator who understood the importance of her husband’s work and could manage the family and commerce in such a way as to allow him full attention to his painting.

Hard on the heels of the Liberty and Eiffel centennials came the 100th anniversary of Vincent Van Gogh’s death, 1990. Another 100 paintings were needed. This towering Dutch/French Post-impressionist is one of Chen’s favorite artists, and a myriad of Van Gogh shards find homes in Chen’s paintings. So Chen went to his easels and in white-hot frenzy painted the 100 paintings commemorating the artist’s passing from the scene. Like the Liberty 100 and the Eiffel 100, the Van Gogh 100 sizzled and snapped. They achieved the homage Chen sought. The paintings were exhibited and widely acclaimed in the Netherlands. And other places.

Chen set out to do 100 paintings about Las Vegas, Nevada, sometimes referred to as “Sin City” because of its gambling, divorce access, and flamboyant visual shatterings. Chen was not doing this as a homage, as he had done in the three previous 100-painting floods, but as an exploration of the Vegas visual cacophony and all its comic and social ramifications. I believe Chen abandoned this pursuit before it reached 100, as he found worthier subjects.

A worthier subject was the 2008 Olympic Games held in Beijing. Again, 100 paintings, maybe more. The best athletes came from all over the world, and China put on a fabulous show. Here again, as in the United Nations work, Chen proved himself a world-class artist. There were tensions, successes, failures in the diverse events. In the totality there was great excitement and great success. Hundreds of photographers shot every event and painters put some of the individual achievements on canvas or computer-generated images, but only Chen succeeded in doing the whole Olympics, capturing and lifting their spirit in visual extravaganza.

Not everyone could be at the Games, but Chen’s work is forever memorialized in the very big book Dr. T. F. Chen’s Art & the Olympics: an Art for Humanity, published in Chinese and English.

Hard on the heals of the Olympics, the excitement in China moved south, to the 2010 Shanghai Worlds’ Fair.

In a lifetime of more than eight decades I have been privileged to view art at International Expositions (World’s Fairs) in San Francisco, Bruxelles, Seattle, Montreal, and New York; at big-time international art fairs in New York, Washington, Paris, Basle, Venice, and Madrid; at hundreds of museums and galleries in the United States, Canada, Europe, and Asia. These have given me a wide, profound, and varied experience, visiting and thinking about man’s artistic means and manipulations over several millennia.

As I think back over these many manifestations, I see that most of them were narrow in scope. ARCO in Madrid, the Basle Art Fair, the Biennale in Venice are all composed of individual pavilions or booths which, usually, fixate on a single painter or a small national group.

Many of the most impressive museum shows to penetrate my lasting consciousness have been one-man retrospectives: Jan Vermeer at the National Gallery, Washington, Emile Nolde in a museum in Tokyo, James Rosenquist at the Houston Museum, and Jasper Johns at the Reina Sophia in Madrid.

Naturally, most of the art pavilions at the world’s fairs tend to be nationalistic, and the most prominent artistic manifestations tend to be architectural: the Atomium in Bruxelles, the Space Needle in Seattle, the Buckminister Fuller Geodesic Dome in New York.

Then came the World’s Fair to trump all World’s Fairs: the massive, encompassing, and pulsating Shanghai World’s Fair of 2010. And unlike all these other manifestations I have alluded to, there was a single artist with the skill, intelligence, and stamina to make a binding interpretation of the entire fair. No souvenir book of photographs (or scholarly examination for that matter) will ever approach the vivacity, beauty, understanding, drama, and intellectual and emotional penetration as the 100 paintings of the Fair done by Dr. Tsing-fang Chen, a Taiwanese American.

Chen is without peer. He is the most intellectually and internationally challenging artist at work anywhere in the world today. Although organized to show the world, including itself, China’s place in the world, the six-month Fair, more than any other ever organized, showed off the global world and its myriad cultures, that whole world of which China is a part. Chen set about to capture the entire spirit of the Fair and its many breath-taking components. So far as I am aware, no one has ever done this for any previous World’s Fair, Art Fair, or museum/gallery manifestation.

Chen accomplished this by studying each pavilion, its outward symbols, its inner meaning, its people, its places, its reality, and its aspirations. Then, using his brilliant mind and his highly developed genius for finding and combining a plethora of icons, he painted a philosophical and esthetic portrait of each of the pavilions, one by one.

When taken as a body, this collection of paintings captures, more than any photographic reportage can ever do, the soul of the Fair.

An icon can be any visual entity. Chen’s genius does not rest just on his ability to choose icons. The genius also demands visual success in depicting and arranging these icons and in the artist’s extraordinary command of compositional color. Chen’s bright and juxtaposed colors jab right into the heart of emotional responses. Few painters have that gift.

|

|

Because of the paintings’ complexities, viewers many not immediately recognize everything they are seeing. That is one of the marvels of great paintings: a viewer can always find something new not seen before. But to help viewers see new things and better understand what they are beholding, Julie Chen, daughter of Tsing-fang and Lucia, has developed an acute and concise way of unlocking keys to many of her father’s paintings. Father and daughter both have gifts for the world, as does the Chen’s son, Ted and his term produce giclée limited edition of Chen’s work.

Chen’s interpretations of the World’s Fair pavilions give us a suite of exciting paintings that have captured the world, one oil at a time. For many viewers, paintings they like most will be the ones that come closest to their own culture. The ones they should study hardest are ones that bring them new understanding. Because of space limitations, from this flow of extraordinary art I can mention only a few for my special comments.

As one would expect, one of the most arresting paintings of these 100 is the depiction of the host city, Shanghai.

Shanghai. Shanghai is composed of four, maybe five, irregularly shaped horizontal bands of images. The top band shows a sky full of fireworks, clear across the width of the painting. Its architectural images begin, on the left, with yellow steps leading up to a red box and then the reversed terrace of an immense overhanging roof of the xxxxxxxxxxxxx. In the center of the widening first band is the Oriental Pearl TV Tower, with its three metallic spheres–a dance hall, a rotating restaurant, and an observation deck– reassembling jewels. Chen has interpreted this structure in bright yellow and red, and it could just as easily be imagined as a rocket ready for liftoff, either way being a symbol of high technological achievement. To the right, in bright colors is a grouping of skyscrapers, which bring to mind the 88-story Jinmao Tower, the 110-story Shanghai World Financial Center, and the 120-floor Shanghai Tower, among many skyscrapers that show just how far the world’s most populous city has come from a sleepy fishing village in just over a century.

This top band ends on the right in a large oval, like a picture frame, across the middle of which is an icon of the new Lupu Bridge, the world’s longest arch bridge. To the left, and closer to the eye, a large river crane, animated and ready to work any of the freighter craft that ply the waterway. The river is painted bright red, color of good luck, and the sky above the bridge is bright sun-light yellow.

The next band down is a closer paean to Shanghai’s passion for skyscrapers, among them the historic Clock Tower Building, which houses Shanghai’s Museum of Art. This band of buildings is depicted in bright, bright colors against dark, dark blue sky. The brightly lit buildings are built shoulder to shoulder and could be imagined as a band of blinding battlements.

The third band changes scale. It is personalized, humanized. It begins with a pretty girl in party dress, then dancing couples enjoying a dance band, and next another pretty girl in red dress playing a stringed instrument.

The fourth and fifth bans are narrow and seem to merge. On the left, in the largest area of green in the painting, is an icon which may suggest a farm, and next to it several old-time, blue-roofed, white buildings along a river. The merged bands end in a large, traditional gate and a summoning of the Yu Yuan Garden, started in 1559 during the Ming dynasty.

France. The painting inspired by the French pavilion is the least complicated of Chen’s Fair outpourings. Its arresting elements are interpretations of two of the most famous sculptures by the most-highly esteemed sculptor of the modern age: August Rodin’s The Thinker, painted in bronze, and The Kiss, painted in gold. The Kiss, the passionate depiction of a couple in love was originally intended as an element of Rodin’s complex Gates of Hell, but the sculptor gave it an independent existence. The Thinker reveals a man in sober meditation battling powerful inner turmoil. The two sculptures and Chen’s selection of them for this painting dramatize a human confict between two necessary forces, passion and thought. By putting the images on the top of a roof, Chen emphasizes their overpowering importance.

Taiwan. This painting is a glorious amalgam of icons, but it is so excitedly pleasing that it is completely unnecessary to recognize any of those icons to appreciate its wonder. In the lower corners are three costumed figures, which many viewers will recognize, and between and above them cartouches jammed with abbreviated images. The top half of the canvas is a deluge of lighted lanterns, each with its own succinct calligraphy, which will give a dimension to the painting for Chinese viewers that the rest of us will not grasp. That will not lessen our appreciation for the wonders of the painting. Even Chen’s signature centered on the base of the painting becomes an integral icon of the composition.

Coca-Cola. Not all of the pavilions were national. Among the many commercial pavilions, Chen has selected Coca-Cola. Coke had modest beginnings. In 1886, John Pemberton, proprietor of Eagle Drug and Chemical, a drugstore in Columbus, Georgia concocted a non-alcoholic beverage after the county passed a law banning alcohol. From that start, Coke bottling plants have sprung up all over the world. Today Coke is sold in 200 countries, making it the most ubiquitous product on the planet. In the process Coca-Cola swallowed up dozens of other beverage makers including Minute-Maid and Fanta and hundreds of products. A visitor to the World of Coca-Cola museum in Atlanta, Georgia can sample 60 of the company’s products, many of which are concocted to accommodate local taste. In this painting Chen has made 54 interpretations of the Coca-Cola bottle from around the world. On the surface, this painting might call to mind American Pop Art, but where artists like Andy Warhol made slavish, repetitive replications of common products, every Chen bottle is vibrantly alive and different. Some are a mixture of icons. This painting is a lot of fun!

Australia–like a large island surrounded by the blue of oceans and wild birds, which suggest freedom. The island itself is more in the shape of Ayer’s Rock than the actual continent. The rock itself is alive with an amalgam of icons which suggest Australia’s varied geography, history, and cultures.

Shanxi summons up history that archaeologically goes back 180 million years up to the current day. Its colors are alive in contrasts and eyeful juxtapositions.

Macau’s colors and composition brim with the excitement of the place, and the Gansu depiction merges the cultural importance of place, dramatized by the dancers, with a sweeping encapsulated view of a modern city, while the Nepal canvas by contrast is one of Buddhist serenity and enlightenment.

One of my favorites, because of its compositional color, is the Shanghai Corporate Joint Pavilion interpretation, even though its icons are fewer and muted. In contrast the dramatic Republic of Korea is so chock-full of icons that there are almost too many to count, making it a painting which will be looked at and marveled over many times.

Lawrence Jeppson has been a renowned international art and art investment consultant, historian, curator, writer, editor, publisher, lecturer, and appraiser for nearly half a century.. Through the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service, the American Federation of Arts, NY’s Museum of Modern Art, and his own Art Circuit Services; Jeppson has been a contributor to more than 200 art exhibitions around the world.